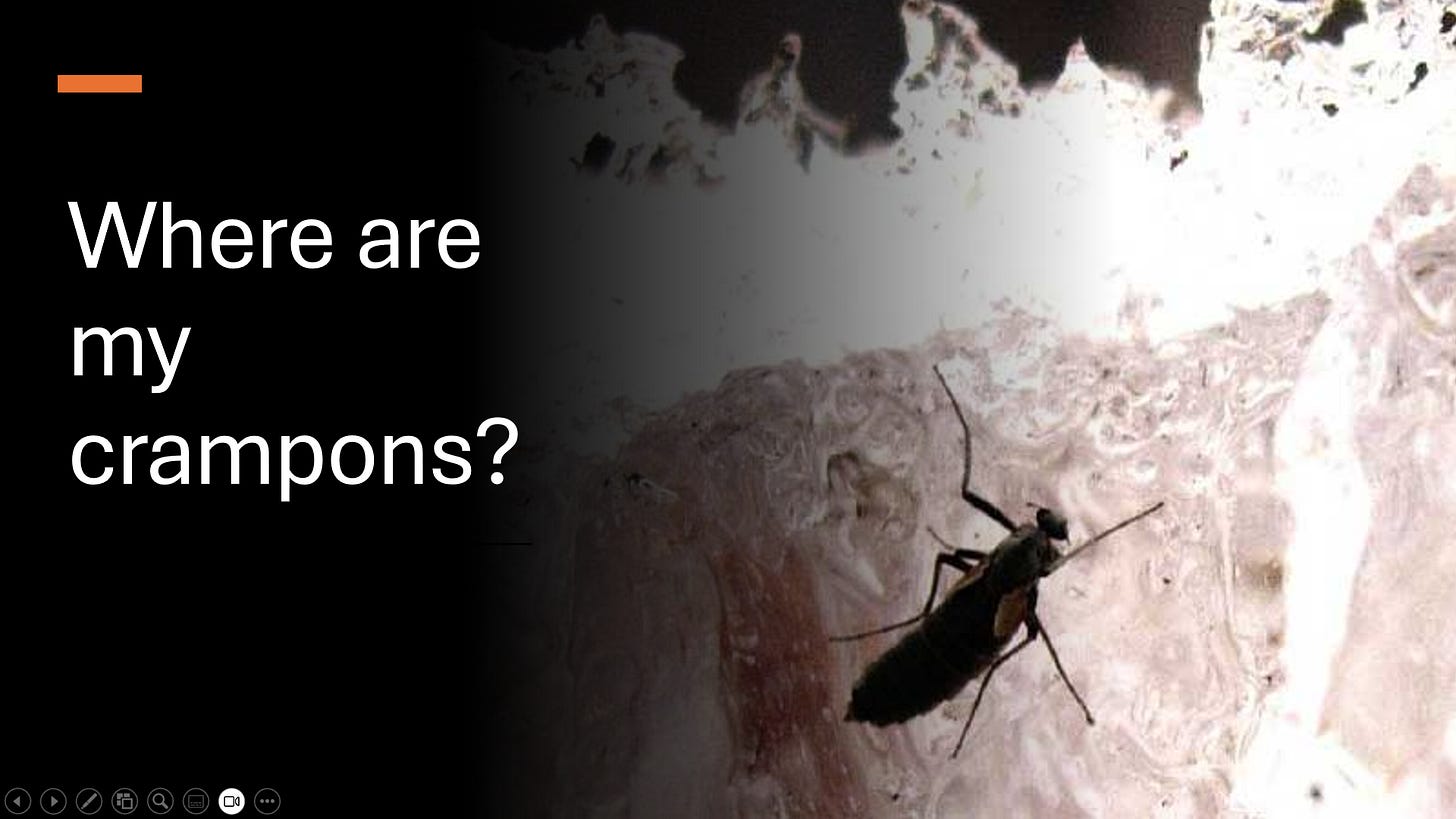

In the Himalayas lives Diamesa, a midge less than half a centimetre long. Dwelling on glaciers, often above 5000 metres, no insect spends it’s life anywhere colder. Unlike their infuriating Scottish cousins, they don’t bite and they can’t fly. You might think they lost out in the insect lottery, but they have one astonishing ability: the females can ice climb. They can clamber up 1500 metres using a sun compass.

The extraordinary skills of animal movement lie at the heart of this week’s Rare Earth: Great Migrations. Let’s start with the insects as their itineraries were new to me. Trillions of them hop the channel from Britain every year, some cross the Indian Ocean, even house flies might migrate. And this isn’t just being blown about. According to Doctor of Insect Migration Will Hawkes, they navigate with some being able to sense wind direction our even plot a course using the Milky Way. I never really thought about where insects go in winter - maybe on top of the wardrobe with my garish summer shirts. My surprise betrays a speciesist bias - believing insects lack the physical and mental capacity for deliberate long-distance travel. They have both.

Many more mysteries of migration could be solved following the launch of the ICARUS satellite in the next few months. A project originally connected to the Russian module of the International Space Station, it’s been delayed by the invasion of Ukraine. But later this year the first of a new range of Icarus satellites will be able to detect signals from much smaller, cheaper, globespanning trackers. Martin Wikelski is the driving force: “We want to have ‘wearables’ on animals. Really small tracking tags that can be seen everywhere. It will give us a biological earth observation system. We can see things, predict things that we couldn’t do in the past because we have all these eyes and ears and noses out there. It’s an Internet of Animals”.

(A linguistic observation: we once described the internet as an ‘Ecosystem of Computers’. Now, the mirror image.)

Whilst our knowledge of migration is blossoming, the migrants themselves are struggling. Habitat loss at either end, hunting, routes blocked by new roads, railways or reinforced frontiers and the tightening ratchet of climate change are all increasingly perilous for birds and animals on the move.

But new research and technology should prove to be the travelling creatures’ ally. Firstly it will reveal how much of our fauna is fluid, shifting around the surface and atmospheric skin of the earth like an elastic film of life. Once we know such fluidity is the norm, we can make our barriers more permeable to the millions who choose to roam. Secondly Author and migration expert David Barrie says it should give us new found respect and admiration for their abilities: “It’s deeply humbling to discover our fellow creatures are actually capable of doing things that we can’t do without the help of technology.” But it’s the power of the new tracking technology to see the individual within the mass that could be really transformative.

It’s an accurate cliche in journalism that one death is a tragedy while one thousand is a statistic. When it comes to human migrants, we feel the anguish from the photo of the single drowned Syrian boy on the beach in Kos. A lone whale in trouble can be the fin that launched a thousand rescue ships. A pig on the run recruits thousands of followers on social media. We have far stronger empathy for characters than groups.

The new satellites will enable scientists, or school children, or campaigners or anyone with a smart phone to follow individual creatures with a tag, right around the clock, wherever they go. Class 3a can choose ‘Willow the Wheatear’ while class 3b can champion ‘Wayne the Wheatear’. Who will get to the Sahara first? Or will the be caught in a hunters trap? It could be an Osprey, a tuna or even a moth, they all have the chance to be the hero in a popular story and such engagement is much harder for politicians to ignore.

All episodes of Rare Earth are on Rare Earth

The whole subject of insect migration is a fascinating one. I was blown away when I learnt that the common marmalade hoverfly migrates all the way from the Mediterranean every year - and then flies back. It's wonderful to imagine these tiny insects making this long journey - that is until you remember that many of the fields they have to cross will be doused in pesticides.

We know a lot and yet at the same time no so little!

A fascinating story.